An end to the data fairy tale (2/2)

In the first part, I addressed the nature of data and our struggles in working with data. I concluded with the observation that despite this struggle, we keep on collecting more and more data. Why are we doing this? An above all, what are the consequences of our data hoarding?

Why do we collect all this data?

As years progress, I ask myself this question more often. The most offered answer is that we want to have data to gain insights. Those insights will enable us to make better decisions in the way we manage our organisations. We want to be able to understand and predict the needs and the behaviours of our stakeholders: of our customers, our suppliers, our employees, our shareholders, our government. But above all, we collect data to be able to influence the decisions made by our stakeholders.

Data is used to establish what information you need to deliver to who. Information of which you suspect it will tilt decisions to your advantage or will lead to favourable actions, like more interaction with your organization. This concerns sales, marketing, product information, experience with purchasing your product or service, the use of your product, but also lobbying for better terms or for legislation. Inside our organisations, we try to align the actions of our employees using this data, to reach the targets we set ourselves.

One of the great misconceptions is that we think that more data will lead to a better representation of reality, and which in turn helps us to reach our targets. More relevant data will only lead to more effectiveness if the added value of acquiring and maintaining that data justifies its costs. Data storage costs next to nothing these days, but the more you need to fish for information in an expanding ocean of irrelevant data, the more expensive your information will be.

Follow up on insights gained from data

What do we do with the insights we gather? Let me start with a positive example, because we do profit from the technological progress.

Our medical knowledge and the use of that knowledge has improved considerably in the past 120 years. Much is based on the methodological gathering of data, which has been accelerated in the last decades by the ease with which we can create data or the ease to put large datasets together. By following scientific principles, progression is made using data. But a scientific process is not a panacea, if only because businesses do not manage their data this way.

Having the data and drawing conclusions is not a sufficient condition. Above all, we need to follow up on those conclusions and this is where we are lacking. Even in the most pragmatic use of business intelligence, I often wonder why we keep ourselves busy with creating and maintaining richly visualized dashboards, because not much is happening with the insights to be learned from those dashboards. And no, automated algorithmic decision-making will not change anything. This is at best a lame excuse to procrastinate.

Despite this observation, the fairy tale of data keeps us under its spell. Why is that? With web 2.0 something new has entered the arena: we stimulate people to produce more data and we seduce them to do so using data. The market value of companies who started this at the turn of this century has exploded. That is an alluring perspective.

Data as a business model

Data as a business model is as old as the written word. Publishers, companies like Bloomberg, they all make money by aggregating data. In this model, the central agent, a journalist or researcher, filters information and makes this information available in a consumable form.

Technology development of the last 20 years made it possible to earn money by letting the information consumer generate the data themselves. The ‘platform economy’ turns the agent from an active player into a passive player. Even this is not a novelty; physical markets with stalls have always worked this way. What is different this time is that anyone can open their own digital stall.

In part, digital platforms exist to sell products and services in the real world, like AirBnB. But in part the objective is to increase traffic on your platform, so you can serve more adds on that platform. We have dubbed these platforms ‘social media’ and it is with social media platforms where the euphoria expressed at the turn of the century has been replaced with cynicism.

Facebook is the example. Facebook is very simple: it is an algorithm that uses your past behaviour and your connections on Facebook, analyses this input and as a result serves you the information that will most likely seduce you to interact with Facebook. Facebook searches for staying power. The reason it has turned into a disruptive force in societies is the result of human nature: we have a more emotional reaction towards information that worries us or makes us angry, indignant or scared. This keeps us longer on Facebook than through information that lightens our mood or amuses us. When we are worried, we start to search for people on Facebook who share our negative emotions. We stay longer on Facebook in search of confirmation and consolation.

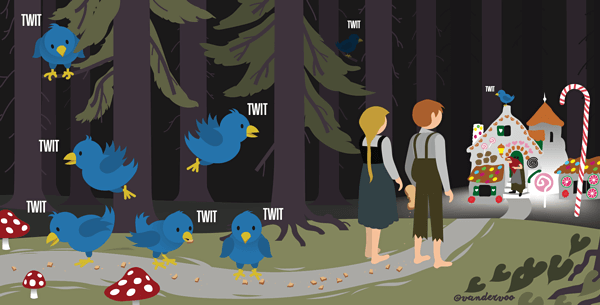

The gingerbread house in the fairy tale of Hansel and Gretel is made up of echo chambers on social media. As it turned out, companies who have a lot of data about us use this data to earn money, not to shape that equalizing democratic Nirwana that was dreamed of. At the same time, we search and dig into this data to find that partial view that “objectively” confirms us in our convictions. Convictions that happen to be driven by egocentrism or greed in most instances.

Again, nothing new under the sun. Far before computers emerged, we exhibited the same behaviour. It is engrained in us. Knowledge is power and data monopolies will deliver you an information advantage. Data is the breadcrumb trail of our behaviour after all and reflects who we are and what motivates us. Economic models would be quite different if information arbitration was not a force in markets.

The lesson to take home from unwanted, and often unintended, consequences of unfiltered data collection, data processing and application is clear, but we do not extend this lesson to how we organise our data in our businesses.

From a fairy tale world to real life

We should leverage the opportunities that data technology offers us and hold ourselves accountable for its side effects. Organisations should shift their focus from technology to data. This sounds like a contradiction or a hollow appeal, but I observe that every time data is discussed in businesses it is almost always in context of a technology implementation. Data processing is seen as a human resources problem: finding enough IT hands.

In my experience, effective application of data demands primarily awareness of what the nature of data is, and the resulting requirements it enforces on processing data. The social media companies show us that massive, automated processing of data causes side effects that are unrelated to the economic purpose for which this data is collected and processed, but which are inherent to data: data mirrors our human urges.

You have to acknowledge the influence of our human urges. Do not assume this is limited to social media, it manifests itself with every instance of data collection and processing. It is an integral part of working with data, as I have shown in part one.

The return of using technology for innovation and the improvement of interaction with all stakeholders will only yield if it is clear to what purpose the data is collected. We need to change the narrative: if you know what you want to achieve, you can start to look for the right data. We need to be more selective in our data acquisition and start to improve the maintenance and the processing of that data.

Hansel and Gretel escaped the gingerbread house in the fairy tale. All’s well that ends well? The problem is that the fairy tale of Hansel and Gretel is a fairy tale. The real world of businesses demands a different approach. For who likes to read more on this subject, I can recommend:

• Connected architecture

• Taming the data beast

• Information overflow asks for curative maintenance

Epilogue

This article was already written when on January 6th American Citizens stormed their Capitol. The emphasis on the role of social media in that event just illustrates my point of view that data reflects our human emotions, and it has always been the case. Data is an artefact, not a raw material. Technology has just widened the reach of data and therefore the potential impact data can have. Both positive and negative.