An end to the data fairy tale (1/2)

It has been 20 years since the DotCom crash and the introduction of the term ‘web 2.0’ in its aftermath. Web 2.0 did put focus on interaction with data.

I have grown up as a ‘data professional’ in the same period. Looking back on those 20 years, I can sum it up in three bullet points:

- Connectivity (internet), the leap in compute power available with low energy use (smart phones) and the drop of storage costs (Cloud) has changed our lives in a very short period, both in a positive and a negative way.

- Despite the introduction of new technologies, data management principles have not changed much and are still badly lived up to. Time and time again, stories are told how new technologies will make those principles obsolete, but time and time again it is proven that those principles are data related, not technology related.

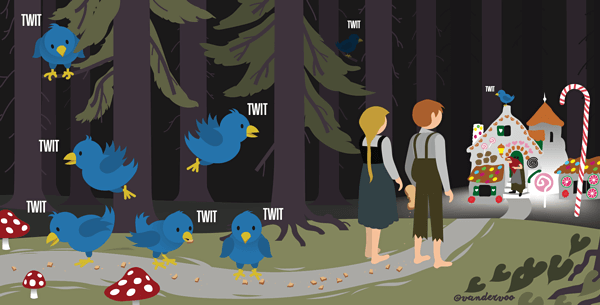

- Promises made with the wide availability of data have turned out to be a fairy tale. Notwithstanding, people still prefer to believe in fairy tales. I presume this is the consequence of the previous points.

Tales of unlimited growth of wealth and democratic Nirwana dominated the first years. The last couple of years, the voices raising concern over the impact of the use of data on our society and economy keep getting louder.

Companies have not been able to propagate knowledge on the nature of data fast enough, and keep up with the pace of data acquisition and data procession, which has exploded. Attention is either given to data acquisition or to the application of data, but the hard part in the middle has been neglected. For 20 years, we have been put to sleep with the fairy tale that if you possess the data, the use of it will evolve naturally.

A fairy tale is often an allegory, packaging a warning about the ugly side of human behaviour. We see human behaviour in everything what data is and in what we do with data, and it reflects both our positive and our negative traits.

In this first part I will help you to understand the nature of data and how humanity has impact on data. But before I do, I will do a live experiment with you.

Live experiment

Look outside. What is the weather like? How much time do you need to assess this? Less than a second?

You will go into a blinded room and lay down on a very comfortable bed. You will be asleep for five hours when I gently wake you.

I will present you data with five minute measures of temperature, rainfall and solar power of the last 24 hours. Can you tell me what the weather looks like?

I add data of pollen index, humidity, UV index and CO2 levels. Can you tell me more precisely what the weather looks like?

I hand you the same figures, but now in real-time. Does it become easier to tell me what the weather looks like?

Are you able to answer my questions with the same speed as the first question? Congratulations, you are a meteorological genius. Or you are fooling yourself.

If this simple experiment clarifies how hard it is to draw conclusions from data for as simple a thing as what the weather looks like outside, how do you do this in your daily work?

What is data?

The experiment maybe clarifies what data is. Different definitions exist of what data is, but I use this one: data is the carrier of information. In the example of the experiment: “Today, it is 23 degrees Celsius, sunny, with a mild breeze from the East” is information, something that paints an image in our head immediately. The temperature reading in degrees Celsius, a measurement of the wind speed and wind direction is data.

Data interpretation and interpretating data

Over the years, I have written often on how the nature of data imposes limitations to what you can do with data or what is reasonable to expect from its application. I have summarized the key points.

Data is a breadcrumb trail

Data reflects our behaviour. There is no such thing as objective data, data is always subjective. Even the reading of a temperature is not objective, but an agreement. Three common accepted agreements are used: the one proposed by Fahrenheit, by Celsius and by Kelvin.

Data is always a subset

Data is partial and never the whole picture. Which breadcrumbs do you collect? If Twitter was your only source of data, what would your interpretation of humanity be?

No two people draw the same conclusion from the same data

If I will conduct my experiment with different people at the same place and point in time, I know I will get different answers. The design of scientific process, in which conclusions are validated and refuted is because of this phenomenon.

The same data leads to different conclusions when the context changes

The same facts will deliver the same outcome, but not the same conclusion. Conclusions are context depended. A lot of people know this, but the significance of that statement is not always understood.

Context in and about data is often shaped by circumstances. Let me explain with an example. You can prove that a coat is 98% moisture resistant in a lab. This measurement is repeatable. Can we conclude this is a great coat? For a walk on the beach on a nice spring day with a chance of showers, probably yes. During a week-long hike in the Scottish Highlands in autumn probably not.

The outcome of the application of data is always determined by circumstances. But during the creation of data, context is often determined by our emotions. It is important to understand that this context is absent from the data when we use it in most cases. A review of a product can be negative because the writer woke up at the wrong side of the bed and not be directly linked with the experience using the product.

Even with a measurement, like outside temperature, context of how the measurement was made is needed in order to do anything useful with the measurement. Meteorological institutions have internationally accepted regulations on how to measure temperature, otherwise data cannot be compared.

An algorithm must be trained not just on the data but also on changing context. That is a serious challenge. The long promised arrival of self-driving cars has not been met yet for this reason. Our brains are wired to deal with changing context. Computer based algorithms are notoriously bad at this. This has a flip side as well: computers will always give you the same output when feeding the same data, while humans do the opposite.

Data processing and data interpretation is a profession in its own right

Every time I read about data being the new gold, or hear people argue with favour about ‘the democratization of data’ in businesses, I think back to my math lessons in school. No other subject let to so much confusion and desperation as statistics did. In my university years, it was the same.

A small part of humanity has an aptitude for modelling data correctly, processing it and having an understanding of what conclusions can be drawn after processing the data, and which conclusions to reject due to insufficient data. Limited data skills lead to more accidents than to progress in the real world.

The data reservoir

Technology lowers the threshold for data collection. Most people I have a conversation with about data, acknowledge that despite the availability, everyday use of that data is an obstacle course. Then why do we keep collecting data and chase the hypes? This is the subject of part two.