Conclusion of the agile with architecture series (7/7)

Agility, based on the principles of the Agile Manifesto is a pragmatic approach to progress in an unknown world. Dave Thomas explains the essence (blog, video):

What to do:

- Find out where you are

- Take a small step towards your goal

- Adjust your understanding based on what you learned

- Repeat

How to do it:

When faced with two or more alternatives that deliver roughly the same value, take the path that makes future change easier.

Attitude and environment of the organisation

The attitude is more important than the rituals. In practice, rituals often have more power than attitude. This has led to the ‘Agile is dead’ movement. It concerns me that the drama of declaring Agile dead has claimed a starring role and this distracts from the problems which organisations are struggling with.

Dan North states why it is a struggle. You are dealing with organisational aims, with alignment, with programmes, with conflicting visions, with big problems and a lack of time. Daily work shows these things stand in the way of organisational agility. How do I ensure the necessary governance, without bureaucracy destroying agility?

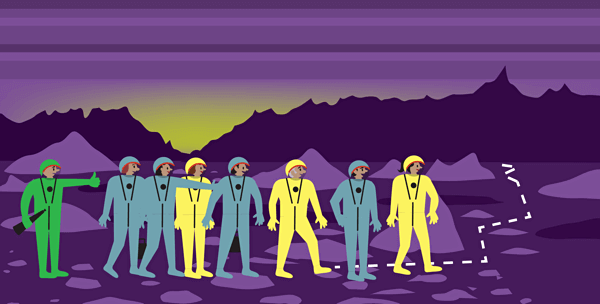

This is a recognizable problem from our practise. Your project is often an agile island.

As an agile island you need to show some agility yourself not only in dealing with the situation but also in being able to adapt at the moment that the organisation is going to change. The transition itself is best formed in the way in which Dave Thomas explains it: in baby steps and constantly adapting to the environment: in an evolutionary way, for want of a better word.

Evolution?

The use of the term ‘evolution’ combined with ‘exploring’ provoked a reaction from Stefan Bexkens, biologist:

Evolution is the term we use for describing changes which life makes to survive the ever-changing circumstances on our planet, with the aim of keeping life intact and multiplying it. Changes in the system evolve partly randomly: mutations emerge [‥], it is a proven system whereby life introduces variations in itself by means of self-correction and constantly testing the environment in which it exists. [‥] Parts which are not changed are discarded, parts which have adapted survive and multiply.

It is always risky to take concepts from one area of science and apply them to another. At an industry or sector level you can observe the same phenomena described above over a long timeline. The environment cannot by influenced by one single organisation.

Where I, as an economist, see a difference between evolution in the biological sense of the word and as applied to change in an organisation’s environment, is that the ‘environment’ is self-created. The environment of an organisation is the net force of behaviours of many individual organisations. The current technology push happens to us, but has been instigated by companies. They are actively working to change the environment. I agree that you cannot steer or explore evolution. The word ‘evolution’ doesn’t completely match, but in terms of communication it is an effective word to use.

Evolution teaches us that survival isn’t a matter of constantly changing or standing still, but a combination of both: Combining best practises from the past with constant adaptation and change, where we can never know for certain what will work well and what not.

Maybe this is the ultimate wake-up call for the need for agility. At the same time, it also shows why it is so very difficult for organisations to implement agility.

In the words of Dave Thomas: not everyone is as far into the unknown territory. Not everyone is able to change his or her understanding of the organisation based on what they have learned, at exactly the same moment. In every organisation, there are different speeds at which organisational change takes place. Some people go on ahead and explore the environment and report on their findings. Based on this you can arrive at a collective decision whether it wouldn’t in fact be better to take a few steps to the left. You need to institutionalise this without making it one person’s responsibility. Learning and changing is a joint working process, not an autonomous process.

The architecture process: part of fitting governance

The architecture process also should fit the principles of agile working, without letting go of the locking pins for crucial sections.

The connection, of enterprise architecture to solution architecture, mustn’t be severed, but the responsibility for filling in between the lines changes during the transition to the agile organisation.

If the organisation itself is not yet completely agile and only a few projects have adopted agile working methods, you will have to accept that the architectural framework from the enterprise architecture and/or domain architecture are still a rigid top down process.

As an architect on the interface between a rigid structure and agility as a way of working, you will have to make your own transition to an agile implementation of the architecture process in your teams. Show that it works by letting go yourself. You can then slowly expand that example to other teams and by making use of the successes you have achieved, make the rest of the organisation enthusiastic.

Learning to let go is an arduous process. In my daily work, I have just as much difficulty with this as everyone else does. The learning experience is however that the results are amazing if you do so and you discover how to motivate a team to take responsibility by making their own choices. Team members are prepared to make their own choices if they are given sufficient safety by agreeing clearly on the leeway they have in making those choices. As long as this fits within the team’s circle of influence, their self-confidence in their abilities will grow.

Make no mistake about what I call the ‘rubbing off’ effect. Team members start applying the framework themselves towards the users or administrators with whom they are working. You don’t need to fight that difficult fight all by yourself.

For a lot of architects I work with, letting go is almost a necessity. I am increasingly noticing that it is precisely the architects who see that the world is changing so fast that it is impossible to keep up. Architects are beginning to accept that they don’t know it all any more.

You can choose to let your head hang in defeat, but I see more of an attitude of looking for cooperation in the organisation to try to understand each other and to work out what the following step should be. It is a challenging time and that makes our work much more fun. It is becoming much more important for architects to convey the importance of architecture thinking, so that small groups of people can autonomously arrive at good decisions and to have an overview of the impact of their choices.

And that is precisely the attitude that you need. The answer to scaling up an agile way of working is not strict governance and neither is it the absence of governance. There is no one single answer, it depends.

The trick is to have a process that constantly evaluates the impact of everything which is heading in the organisation’s direction. If there is any impact, then this needs to be absorbed at the right level. That needs to be routine and it is exactly this routine which makes you agile.

The last paragraph is the essence of what I have been trying to make clear in more detail over the last six parts.

That’s all folks?

There are many more aspects in making and keeping an organisation agile.

The architecture process is only one aspect of your organisation’s total governance. Agility places demands on your technical architecture, on the way in which you deal with data modelling. We have gained extensive experience in this aspect at Free Frogs.

There is more than enough to write about this subject, so you can expect more about it to arrive in this blog this year.

Thanks

I am very grateful to my colleagues Erwin Pilon, Kees Molenaar, Marcel van den Hoff and Tri Mahabali. During a review process, they gave me very valuable feedback and helped make illegible text legible.

A special word of thanks is due for Marnix Dalebout. More than 15 years of working together to translate the ideas behind agile working into intelligence architecture, has resulted in a continuous conversation about and search into how we can do our work more effectively. The insights shared in this series are just as much his as mine.